Barrett’s esophagus is a condition marked by an abnormality in the lining of the lower esophagus. It is believed to be due to severe, longstanding, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Significantly, most people with GERD have no such abnormality. Nevertheless, the presence of Barrett’s esophagus is an important observation since those who have it are at greater than normal risk of developing cancer of the esophagus.

Anatomy

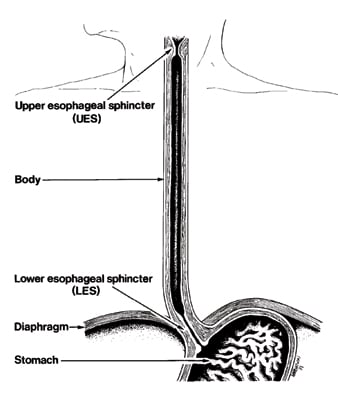

Figure 1 illustrates the anatomy of the esophagus. Normally, the esophageal lining (the epithelium) consists of flat, layered cells similar to those in the skin. This squamous epithelium stops abruptly at the junction of the esophagus with the stomach near the lower end of the lower esophageal sphincter. The epithelium of the rest of the gut, down to the anus, consists of a single layer of side-by-side rectangular cells, which is called columnar epithelium.

In some people, the transition from squamous to columnar epithelium occurs higher within the esophagus than normal. There may also be islands of columnar epithelium above the normal junction of the stomach and esophagus.

The figure illustrates a normal esophagus, the organ that connects the mouth to the stomach. The lining (epithelium) of the esophagus down to the lower esophageal sphincter is normally squamous. However, in Barrett’s esophagus, columnar epithelium extends to varying degree up into the esophageal body.

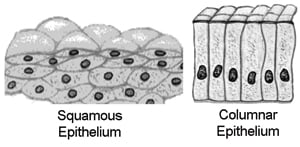

Figure 2 illustrates the difference between squamous and columnar epithelium.

Barrett’s columnar epithelial cells may resemble those of the colon, small bowel, or stomach. One esophagus may contain several types. The process of cell change from flat, layered squamous to tall columnar epithelium is an example of metaplasia.

Columnar cells are more resistant to acid and pepsin and the metaplasia may be a defense against refluxed acid. In Barrett’s, the cells are usually of a type referred to as specialized columnar epithelium (a distinctive type of intestinal metaplasia). They include mucus cells, and have a tendency to resemble cells found in the small intestine.

Squamous epithelium, seen in the esophagus and skin, consists of layers of flat cells. Columnar epithelium, characteristic of the rest of the gut, consists of a single layer of tall, rectangular cells. In Barrett’s esophagus, the normally squamous epithelium of the lower esophagus becomes replaced with various types of columnar cells, that may predispose to a type of cancer known as adenocarcinoma.

Diagnosis

Barrett’s esophagus can only be seen through an endoscope (a thin, flexible, device used to look inside the body) but always requires surgical tissue specimens (biopsies) for diagnosis.

Normally, the point where the red tissue that lines the stomach (gastric mucosa) ends and the paler pink squamous esophageal mucosa begins sharply demarcates the junction between the stomach and the esophagus.

In Barrett’s esophagus, the separation is above its normal position. It may reach upwards in tongue-like projections of gastric tissue into the esophagus, as islands of gastric mucosa amongst the (esophageal) squamous, or may involve the whole circumference of the esophagus to a certain level.

This abnormal columnar tissue may extend to any level within the esophagus, even as high as the upper esophageal sphincter. The doctor, through endoscopy, can normally recognize the abnormal (metaplastic) tissue, but an overlying inflammation due to reflux may obscure it. Peptic ulcers [sores or erosions] sometimes occur in Barrett’s epithelium and can be large.

Esophageal cancer

The importance of Barrett’s esophagus is its significantly increased risk of esophageal cancer, though the incidence of this cancer remains low. The exact figure is difficult to obtain because an unbiased estimate of the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus is unavailable. However, a 2011 study in the general population suggested a rate of 0.12% annually [Hvid-Jensen et al, N Engl J Med, 2011].

The risk is real and is further increased by factors such as tobacco and alcohol use. Also, the risk is greatest if the metaplastic epithelium is of the specialized columnar type and if the area of metaplasia is large.

Changes can be detected in the Barrett’s tissue of those more likely to develop cancer. Called dysplasia, these changes are an indication for repeated endoscopy and biopsy. Dysplasia is an abnormal condition in which cells may have altered shape or may divide in a manner that alters the appearance of the tissue or organ.

The degree of change ranges from minor to significant changes (low-grade), to serious or very abnormal changes (high-grade) dysplasia. The presence of inflammation of the Barrett’s tissue may be confused with dysplasia, but resolves with treatment. Failure of dysplasia to regress with treatment should prompt close surveillance (repeated endoscopy).

One of the esophageal cancers is squamous cell carcinoma that develops (often also with the help of tobacco and alcohol) in the normal squamous cell lining of the esophagus. This cancer may be treated by radiotherapy or surgery.

The cancer developing in the columnar cells of Barrett’s epithelium is called an adenocarcinoma, and resembles stomach cancer. The incidence of this cancer is increasing in North America especially in white males, and adenocarcinomas do not respond well to radiation treatment.

Treatment of Barrett’s esophagus

The management of newly discovered Barrett’s esophagus has three objectives:

-

-

- The treatment of the tissue damage in the esophagus (esophagitis)

- Elimination of Barrett’s tissue in patients with dysplasia

- The early detection or prevention of cancer through a surveillance program

-

Medication Treatment

Esophagitis is commonly treated with medications to control acid production or secretion (primarily proton pump inhibitors). Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are recognized as the most powerful and effective drugs used to inhibit acid secretion and allow healing of tissue damage in the esophagus. Early detection or prevention of cancer is discussed below.

Guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology recommend periodic check-ups (surveillance) or action as follows:

| In the presence of Barrett’s esophagus with: | Recommendation: |

|---|---|

| No dysplasia | Endoscopic examination every 2–3 years |

| Low-grade dysplasia | Endoscopic examination every 6 months for one year, and if negative results, once per year thereafter. |

| High-grade dysplasia | Expert confirmation (second opinion). Depending on individual factors doctor may recommend selective resection (surgical removal of the esophagus) or ablation therapy (endoscopic therapies that remove or destroy the Barrett’s tissue). Or endoscopic examination every 3 months. |

Elimination of Barrett’s tissue

Recently, several tools that can eliminate (ablate) Barrett’s tissue have been introduced. They include freezing (cryo) or burning (radiofrequency) the Barrett’s tissue. [Careful post-treatment surveillance is still required with these treatments. Small areas of Barrett’s esophagus may be buried beneath newly formed squamous tissue in the esophagus. Continued research is needed.]

Early detection or prevention

How can we prevent cancer from occurring in Barrett’s esophagus? Early detection and prevention of cancer are difficult. Since Barrett’s esophagus is believed to result from chronic GERD, vigorous treatment of that condition has been tried. However, while proton pump inhibitors improve the esophagitis and heartburn, they fail to reverse the Barrett’s metaplasia. Anti-reflux surgery has also failed to reverse Barrett’s tissue. Ablation (elimination) of Barrett’s tissue is presently indicated only in those with dysplasia.

Studies have suggested that risk of esophageal cancer is amplified by factors that either increase reflux (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, high dietary fat, chocolate, caffeine, obesity, certain medications); or are genotoxic, which means capable of damaging DNA (e.g., a diet low in vegetables and fruits, tobacco use, dietary nitrosamines found in cured meat).

Measures that may be protective include lifestyle modifications emphasizing controlling reflux, tobacco cessation, improvements in diet (e.g., less fat, more fruits and vegetables), and weight loss if you are overweight.

Surgical removal of the abnormal tissue would remove the cancer risk. However, most people with Barrett’s esophagus never develop esophageal cancer, and such major surgery cannot be justified unless cancer is proven to be imminent. The challenge is the timely discovery of those with Barrett’s esophagus that are at risk.

Cancer detection programs employ periodic endoscopic examination of the esophagus and the procurement of tiny tissue samples (biopsies) for the pathologist to examine. For this discussion, Barrett’s esophagus is defined as a junction of squamous and columnar epithelium that is three or more centimeters above the normal anatomical junction of the esophagus with the stomach, or the presence of specialized columnar epithelium at any level of the esophagus.

In newly detected cases the abnormal segment is systematically biopsied (in four quadrants at 2-cm intervals within the metaplastic esophagus). If there is doubt about the pathologist’s interpretation of the biopsies, they should be promptly repeated.

Severe dysplasia seen at multiple sites in a young person may prompt the physician to suggest surgical removal of the lower esophagus (esophagectomy). For those individuals for whom surgery is considered too risky, close observation at three-month intervals may be a safer alternative.

If low-grade dysplasia persists after adequate treatment of the esophagitis, the patient should be followed yearly with endoscopy and biopsy. Otherwise, all affected persons should be endoscoped and have the affected area biopsied at 18 to 24 month intervals.

Not all the experts subscribe to such an aggressive and expensive program, nor has it yet been shown to save lives or improve quality of life. However, few question the ominous implications of severe or “high-grade” dysplasia. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus should not have the condition ignored, so a surveillance protocol is indicated for those who have the condition.

Risk Factors and Protective Factors

Anything that increases a person’s chance of developing a disease is called a risk factor; anything that decreases a person’s chance of developing a disease is called a protective factor. Some risk factors can be avoided (e.g., diet or lifestyle), but some cannot (e.g., genetics). Avoiding risk factors and increasing protective factors that can be controlled may decrease chances of developing a disease.

Summary

Barrett’s esophagus consists of a change in the normally squamous lining of the lower esophagus to columnar epithelium (metaplasia). Unless there is severe esophagitis, this change can be recognized during an endoscopy. Because there is an increased risk of esophageal cancer in people with Barrett’s esophagus, most physicians recommend regular endoscopy and biopsy of the altered tissue to detect pre-cancerous changes (dysplasia). If these changes persist and are severe (high-grade dysplasia), aggressive treatment is necessary to prevent development of adenocarcinoma.

Adapted from IFFGD Publication: Barrett’s Esophagus by W. Grant Thompson MD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Canada; and Ronnie Fass, MD, Chair, Division of GI and Hepatology, Metro Health Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.