The following article discusses surgical treatments for GERD.

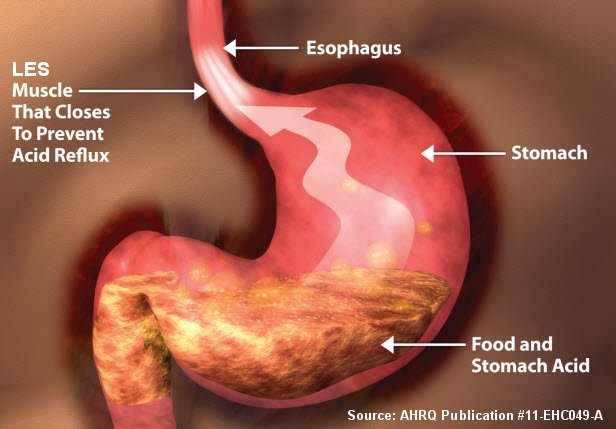

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as the back-flow of stomach contents into the esophagus causing undesirable symptoms and potentially resulting in esophageal damage.

Symptoms of GERD

The most common symptom of GERD is heartburn. This is an uncomfortable burning sensation felt in the middle of the upper abdomen and/or lower chest. Other typical symptoms include difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and regurgitation of fluid into the esophagus. In some cases fluid may even reflux into the mouth. People with GERD also may develop other, atypical (extraesophageal) symptoms such as hoarseness, throat-clearing, sore throat, wheezing, chronic cough, and even asthma. Many persons suffer from extra-esophageal reflux symptoms for quite some time before a causal relationship with GERD is established. This is at least partly related to the fact that there are many other causes for these kinds of symptoms other than GERD.

Causes of GERD

GERD is caused by improper mechanical function of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The LES is a ring of muscle that surrounds the junction of the esophagus and the stomach and acts as a valve. When functioning properly, this valve opens when swallowing to allow passage of food from the esophagus into the stomach. The valve then closes and acts as a barrier to keep stomach contents from refluxing into the esophagus. In people with GERD, the LES does not properly close resulting in back-flow of gastric contents. It is the back-flow of gastric contents that cause the symptoms of GERD.

In many people, there is no obvious reason for failure of the LES. The LES itself may be weak or its supporting structures (from the esophagus, the diaphragm, or the angle the esophagus enters the stomach) may be inadequate. In others, there may be lifestyle or behavioral factors that stress the LES and contribute to its failure. These factors include:

- obesity,

- smoking,

- alcohol use,

- a high fat diet, and

- consumption of carbonated beverages.

Additionally, a hiatal hernia can lead to GERD. Hiatal hernia results when the LES moves above the diaphragm, a sheet of muscles that separates the abdominal and chest cavities. When the LES moves into the chest, it is less able to prevent reflux. Finally, GERD symptoms can be compounded by defective clearance of acid and fluid from the lower (distal) esophagus due to esophageal damage or esophageal motility disorders.

Learn more about surgery for hiatal hernia and GERD

Medical Management of GERD

Lifestyle Changes – The treatment of GERD begins with behavioral and lifestyle changes. Reduction of symptoms can be achieved in most individuals with several modifications. These include:

- weight loss,

- avoidance of carbonated beverages,

- abstinence from smoking,

- reducing alcohol and caffeine intake,

- avoiding “trigger” foods (spicy foods, citrus or acidic foods),

- maintaining a low fat diet,

- avoiding eating or drinking several hours before going to bed, and

- elevating the head of the bed at night.

Medications – If symptoms are severe, or if symptoms persist despite lifestyle modifications, then medication should be considered. Acid reducing medications include proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine H2-receptor blockers (H2 blockers). It is important to understand, these medications do not stop reflux from occurring. However, they are often effective in reducing the amount of acid in the gastric fluid. In most people, acid reduction is enough to relieve or even eliminate symptoms of GERD. Medications are also very effective in treating complications of GERD such as esophagitis. In some people, however, long-term use of PPIs may be associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures of the hip, wrist, and spine. Although many of the most effective acid reducing medications are available over-the-counter, long-term use of greater than 2 weeks or failure of medications should be discussed with a physician.

Surgical Treatments of GERD

Surgical therapy is also an option for the treatment of GERD. The main indication for surgical therapy is failure of medical management when symptoms persist despite appropriate medical therapy. Another indication for antireflux surgery is personal preference. Some people do not want to take lifelong acid suppression medication or have too many side-effects from these medications and may want to consider antireflux surgery.

Required Testing Prior to Antireflux Surgery

Several tests are necessary to determine if a person is a good candidate for antireflux surgery. The purpose of these studies is to:

- identify objective evidence of reflux,

- correlate reflux with symptoms, and

- evaluate for other coexisting diseases that may be contributing to symptoms.

In general, all patients should have an upper endoscopy. Additional testing includes a 24-hour pH test with impedance, and an esophageal manometry study. Often, a patient will also have a contrast esophagram in the early stages of their evaluation.

Upper Endoscopy – An upper endoscopy or EGD involves placing a small camera through the mouth and into the upper gastrointestinal tract allowing evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine (duodenum). This is generally done as an outpatient procedure under mild to moderate sedation. The purpose of endoscopy is to evaluate for reflux-related damage, to assess the integrity of the LES, and to identify any alternative or coexisting disease processes that may be contributing to symptoms. Long-term exposure of the esophagus to gastric acid can cause damage such as erosion (esophageal ulcers), inflammation (esophagitis), scarring (esophageal stricture), and changes to the inner esophageal lining (Barrett’s esophagus). During an endoscopy, potential abnormalities such as gastritis, peptic ulcers, polyps, nodules, and infections can also be assessed. Tissue samples (biopsies) of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum are often obtained during this procedure. Stomach tissue samples are often tested for an infection called H. pylori.

24-Hour pH Test – A pH study involves a thin, soft silastic tube (catheter) inserted through a patient’s nose and into the distal esophagus above the LES. Sensors on the tube detect and record acid reflux episodes. The device is also designed to record when a patient feels symptoms to determine if these symptoms correlate with reflux episodes. This test is conducted over a 24-hour period on an ambulatory patient who is off acid-suppression medications. During the test the individual is able to continue routine activities. One version of this test involves the attachment of an acid sensing chip on the lining of the lower esophagus. This is known as a Bravo probe and has the advantage of avoiding insertion of a tube through the patient’s nose.

Esophageal Impedance pH Study – Many physicians are also utilizing the 24-hour esophageal impedance study for evaluation of reflux in certain patients, which involves the same procedure described above (a tube passed through the nose into the esophagus). Esophageal impedance detects fluid reflux whether or not it is acidic. Both acid and non-acid reflux events are therefore measured. Individuals may have non-acid or weakly acid reflux, or continue to have symptoms despite high dose acid suppression and the impedance study can provide valuable information in these cases. (The Bravo study probe only measures acid so cannot be used for the impedance study.)

Manometry – Esophageal manometry measures the motor or contractile function of the LES and the esophagus. This test is mainly used to evaluate for any underlying esophageal motility disorders that may be contributing to a person’s symptoms (such as achalasia).

Antireflux Surgery

Surgery for GERD is known as antireflux surgery and involves a procedure called a fundoplication. The goal of a fundoplication is to reinforce the LES to recreate the barrier that stops reflux from occurring. This is done by wrapping a portion of the stomach around the bottom of the esophagus in an effort to strengthen, augment, or recreate the LES valve. The most common type of fundoplication is a Nissen fundoplication in which the stomach is wrapped 360 degrees around the lower esophagus. There are also a variety of partial fundoplication techniques. As the name suggests, these techniques involve a wrap which does not go entirely around the esophagus. The Nissen fundoplication is almost always chosen to control GERD.

Antireflux operations today are most often performed using a minimally invasive surgical technique called laparoscopy. The technique utilizes a narrow tube-like camera and several long, thin operating instruments. In the operating room, the camera and instruments are inserted into the abdomen through several small (less than 1 cm or ½ inch) incisions on the abdominal wall. The operation is then performed within the abdominal cavity using camera magnification. The benefit of this type of minimally invasive technique is that it results in less pain, a shorter hospital stay, a faster return to work, smaller scars, and a lower risk of subsequent wound infections and hernias.

Learn more about laproscopic surgery

If the surgery cannot be safely completed using laparoscopy, the operation is converted to a traditional open procedure that involves an incision in the upper abdomen. The open technique is both safe and effective, but it sacrifices the aforementioned benefits of laparoscopy.

In either case, surgery should be performed by a specialist with appropriate training or high volume experience.

Recovery from Antireflux Surgery

After surgery, patients are generally admitted to the hospital for 1–3 days. This observation period is to ensure that the patient is free of nausea and vomiting, and able to tolerate drinking enough liquids to maintain hydration. Patients are generally discharged on a soft, pureed, or a liquid diet.

The dietary restrictions after surgery can vary, but in general, patients should expect to slowly advance to a solid diet over a 2–8 week period of time. The dietary restrictions are slowly lifted after several weeks and the patient progresses through a soft and/or post-Nissen diet. Many surgeons recommend that their patients only take crushed or liquid medications for several weeks after surgery.

Side Effects and Complications of Antireflux Surgery

Although antireflux surgery is considered both safe and effective, complications and undesirable side effects can occur. Below is a brief description, but these should be discussed with your surgeon before undergoing an operation.

After a fundoplication, some patients report difficulty belching or a sensation of abdominal bloating. This is rarely severe and generally resolves within the first 6 months after surgery. Some patients may also report an inability to vomit, and some patients also report increased flatulence and diarrhea.

Rarely, patients also report long-lasting dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, after surgery. While some degree of dysphagia is common immediately following surgery due to swelling in the area of the operation, this usually resolves within several weeks after the surgery. Dysphagia is the reason most surgeons recommend a liquid or soft diet after surgery and advise patients to eat slowly, take small bites and chew food well. Persistent or long-standing dysphagia can usually be treated with endoscopic dilation and in rare cases a revision of the original operation may be required.

Complications can result from general anesthesia, bleeding, infection, and/or injury to nearby organs. Nearby organs include the stomach, esophagus, spleen, liver, vagus nerves, aorta, vena cava, diaphragm, lungs, and heart.

Overall, laparoscopic antireflux surgery when performed by an experienced surgeon is exceptionally safe and any significant operative complication is quite unusual.

Outcomes after Antireflux Surgery

The outcomes after laparoscopic antireflux surgery are generally excellent. In both short-term (1–5 years) and long-term studies (5–10 years), the vast majority of patients report effective symptom reduction, a high level of satisfaction, and an improved quality of life after having the surgery. Nearly all patients are taken off of reflux medication after surgery. The most telling factor is that patients have consistently reported that if they were to do things over, they would again make the decision to undergo antireflux surgery.

The most important factor in determining if a patient will experience an improvement or resolution of their GERD attributed symptoms is to ensure with a great deal of certainty that these symptoms are actually from GERD. For this reason, a proper evaluation before the operation is imperative. For extraesophageal symptoms such as cough and hoarseness, the many other conditions not related to GERD are possible. In many of these cases, appropriate testing and multidisciplinary evaluation with a surgeon, a gastroenterologist, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose, and throat specialist), and a pulmonologist (lung and respiratory specialist) is important in confirming the diagnosis and ruling out other potential causes.

Reflux in People who are Morbidly Obese

Obesity is a major risk factor for GERD. Weight loss has been demonstrated to consistently lead to an improvement in GERD related symptoms in obese patients. Some morbidly obesepatients with GERD who fail appropriate medical management may see a surgeon for a discussion about antireflux surgery. A laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in a morbidly obese patient is quite difficult. Some data suggests that the failure rate of a laparoscopic Nissen in morbidly obese patients is increased compared to the non-obese. Bariatric (weight-loss) surgery has been demonstrated to be effective in controlling and curing GERD in some patients. Morbidly obese persons who have GERD that is uncontrolled by medical therapy and who meet the criteria for antireflux surgery should talk to their doctor about the option of bariatric surgery.

Emerging Therapies

Although the laparoscopic fundoplication is the current standard of surgical care, there is an evolving array of exciting new endoscopic, incisionless treatments for GERD under evaluation. The newest therapy is the transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF). This is an incisionless fundoplication performed with an endoscope that is inserted through the mouth and into the stomach. Short-term results appear favorable in carefully selected patients; however, long-term studies have not yet been completed. Many emerging therapies for GERD are still being evaluated under experimental protocols and can only performed at selected research centers.

In March 2012 the FDA approved the LINX System, comprised of a surgically implanted device to help manage reflux, for people with GERD who have not been helped by other treatments.

Summary

GERD is the most common digestive disorder for which patients seek medical care. Approximately 10% of Americans suffer from daily symptoms or take medications to manage these symptoms on a daily basis. In most patients who do not tolerate medical therapy or in patients who have inadequate or incomplete relief of GERD symptoms from appropriate medical therapy, antireflux surgery – performed by experienced surgeons and in appropriately selected patients – is a safe and effective option.

Adapted from IFFGD Publication: The Surgical Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) by Andrew S. Kastenmeier, MD, and Jon Gould, MD, Division of General Surgery, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI. Published in Digestive Health Matters, Vol. 21, No. 3.